New Delhi [India], December 25: Christmas in Calcutta did not arrive as a fragile import. It landed like a citywide performance and refused to stay indoors.

By the late eighteenth century, Calcutta had already detached Christmas from its English stiffness. Colonial commentators noticed it early. An 1894 article in The Saturday Review openly complained that English Christmas traditions had become formulaic, while Calcutta had turned the festival into something freer, louder, and frankly more enjoyable.

By then, the city was already calling it Burrah Din. The Big Day. No apology needed.

This was not mimicry. It was an adaptation. Calcutta did not chase snowflakes or fireplaces. It worked with light, food, music, and streets. The result was a ritual that made sense to a tropical port city with global connections and zero patience for narrow definitions of celebration.

From Artillery Salutes to Marigold Gates

The idea that Christmas in Calcutta began as a small colonial club event is simply wrong.

Records show large-scale celebrations as early as 1780. James Augustus Hickey, never one to exaggerate subtly, documented Christmas Day that year as a full ceremonial affair. Governor-General Warren Hastings hosted an official breakfast, followed by what Hickey described as an extravagant dinner attended by elite guests. Artillery salutes thundered from Lal Dighi. The evening ended with music, illumination, and a ball.

This was not a quiet holiday. It was a civic theatre.

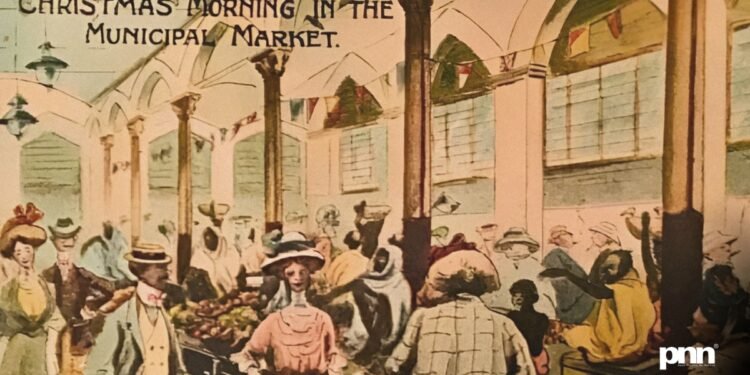

Eliza Fay’s letters from the same period provide sensory details. Large plantain trees stood at entrances. Gates were decorated with flowers. Fish and fruit arrived in abundance. Native servers handled logistics. Christmas had already crossed racial and cultural lines.

By the mid-nineteenth century, decorations blended British custom with Indian symbolism. Plantain leaves signalled abundance. Marigolds appeared alongside laurel wreaths. Lamps replaced candles. Gordon-Cumming later observed that locals embraced Christmas aesthetics with enthusiasm because feasting was a universal language.

Calcutta did not dilute Christmas. It expanded it.

How Commerce Turned Christmas into a City Event

If religion introduced Christmas, commerce made it unstoppable.

By the 1850s, newspapers were already running Christmas Eve advertisements. The Bengal Hurkaru promoted Stilton cheese and turkey at the Great Eastern Hotel. Luxury stores stocked imported foods, gifts, and decorations. Governors-General chose Calcutta as their winter base precisely because the city knew how to host.

By the 1880s, Christmas shopping had become a seasonal economy. The Statesman described illuminated streets, packed luxury stores, and shoppers who stayed out until dawn. New Market emerged as a central node, bringing together Jewish and Armenian confectioners and Indian crowds.

This was not elite-only consumption. It was urban participation.

Plum cakes, brandy-soaked puddings, pastries, and sweets became heirlooms. Recipes passed through families and communities. Christmas food in Calcutta became a memory you could taste.

Clubs, Hotels, and the Business of Celebration

Calcutta professionalised Christmas before most cities even tried.

Hotels like the Great Eastern, Grand Hotel, Firpo’s, Peliti, and Bristol ran elaborate Christmas buffets and entertainment weeks. European clubs organised lunches, dinners, and garden parties that doubled as social calendars.

The Calcutta Club, founded in 1907, became a powerful venue. Viceroys dined there. Princes attended lunches. Garden parties followed Christmas dinners. Even after the capital moved in 1911, the city did not lose its Christmas gravity.

Entertainment scaled with confidence. Circuses arrived by December. Wrestling exhibitions, theatre shows, magic acts, river cruises, polo matches, horse races, and cricket games filled the season. Royal Circus shows ran from mid-December with nearly a hundred animals by the 1920s.

Christmas was no longer a date. It was a season.

Cakes, Cards, and Cultural Memory

One of Calcutta’s most underestimated contributions to Christmas was its intellectual and visual culture.

Christmas cards printed between 1908 and 1912 by Thacker, Spink & Co featured humour, local scenes, and irreverent illustrations. They were not pious images of European winters. They were distinctly Calcutta creations. The anonymous artist signing as Geo. D understood the assignment.

Then came spectacle baking. Peliti produced monumental cakes, including replicas of Delhi monuments. In 1889, a twelve-foot Eiffel Tower cake stunned the city weeks before Christmas Eve. This was culinary confidence.

After World War I, Christmas gifts reflected modernity. Gramophones, phonographs, and music boxes dominated wish lists. Department stores competed aggressively with discounts and glossy brochures.

Christmas in Calcutta was always contemporary. It evolved with technology, taste, and aspiration.

Christmas After Empire

The empire left. Christmas stayed.

By the late 1950s, Christmas in Calcutta had become a civic tradition rather than a colonial residue. Historian accounts describe it as a cultural institution with broad participation.

Anglo-Indians played a visible role, sustaining architecture, schools, clubs, and charitable events. But they were not alone. Muslims supplied bakarkhanis. Jewish bakeries anchored dessert culture. Chinese kitchens in Tangra became late-night magnets.

The Bengali public embraced the festival fully. The name Boro Din says everything. It was never about theology alone. It was about scale, warmth, and shared time.

Bow Barracks turned into a street-level spectacle. New Market became a human tide. Tangra steamed with food and noise. Christmas moved from halls to sidewalks.

Why the City Still Shows Up

Christmas in Calcutta survives because it functions as civic glue.

It stages neighbourhood solidarity. It triggers diasporic returns. It activates memory without freezing it. It allows multiple communities to participate without forcing uniformity.

This is not nostalgia tourism. It is a living practice.

Schools host concerts—clubs host lunches. Charitable organisations stay busy through December. Institutions like Loreto Entally and the All India Anglo-Indian Association continue to show visible leadership.

The city shows up because Christmas here is not borrowed. It is owned.

Calcutta did not inherit Christmas passively. It rebuilt it publicly, commercially, and emotionally. That is why the lights still go up. That is why people still call it the Big Day. That is why the streets still fill.

Cities do not keep traditions alive by accident. They do it by making them useful. Calcutta figured that out over a century ago.

Kolkata Christmas Festival – West Bengal Tourism

https://www.wbtourism.gov.in/christmas